In this blog post, we describe the first peer-reviewed research paper that explores accelerating the hybrid of PyTorch DDP (torch.nn.parallel.DistributedDataParallel) [1] and Pipeline (torch.distributed.pipeline) - PipeTransformer: Automated Elastic Pipelining for Distributed Training of Large-scale Models (Transformers such as BERT [2] and ViT [3]), published at ICML 2021.

PipeTransformer leverages automated elastic pipelining for efficient distributed training of Transformer models. In PipeTransformer, we designed an adaptive on-the-fly freeze algorithm that can identify and freeze some layers gradually during training and an elastic pipelining system that can dynamically allocate resources to train the remaining active layers. More specifically, PipeTransformer automatically excludes frozen layers from the pipeline, packs active layers into fewer GPUs, and forks more replicas to increase data-parallel width. We evaluate PipeTransformer using Vision Transformer (ViT) on ImageNet and BERT on SQuAD and GLUE datasets. Our results show that compared to the state-of-the-art baseline, PipeTransformer attains up to 2.83-fold speedup without losing accuracy. We also provide various performance analyses for a more comprehensive understanding of our algorithmic and system-wise design.

Next, we will introduce the background, motivation, our idea, design, and how we implement the algorithm and system with PyTorch Distributed APIs.

- Paper: http://proceedings.mlr.press/v139/he21a.html

- Source Code: https://DistML.ai.

- Slides: https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1t6HWL33KIQo2as0nSHeBpXYtTBcy0nXCoLiKd0EashY/edit?usp=sharing

Introduction

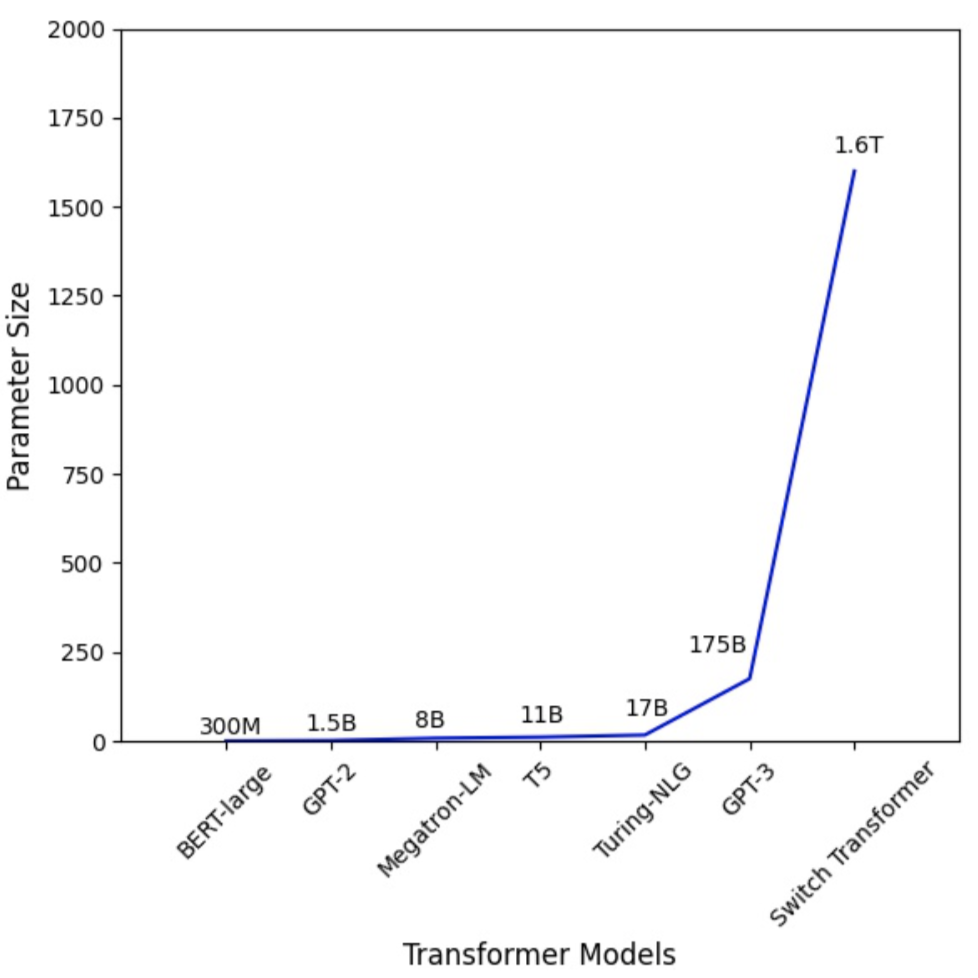

Figure 1: the Parameter Number of Transformer Models Increases Dramatically.

Large Transformer models [4][5] have powered accuracy breakthroughs in both natural language processing and computer vision. GPT-3 [4] hit a new record high accuracy for nearly all NLP tasks. Vision Transformer (ViT) [3] also achieved 89\% top-1 accuracy in ImageNet, outperforming state-of-the-art convolutional networks ResNet-152 and EfficientNet. To tackle the growth in model sizes, researchers have proposed various distributed training techniques, including parameter servers [6][7][8], pipeline parallelism [9][10][11][12], intra-layer parallelism [13][14][15], and zero redundancy data-parallel [16].

Existing distributed training solutions, however, only study scenarios where all model weights are required to be optimized throughout the training (i.e., computation and communication overhead remains relatively static over different iterations). Recent works on progressive training suggest that parameters in neural networks can be trained dynamically:

- Freeze Training: Singular Vector Canonical Correlation Analysis for Deep Learning Dynamics and Interpretability. NeurIPS 2017

- Efficient Training of BERT by Progressively Stacking. ICML 2019

- Accelerating Training of Transformer-Based Language Models with Progressive Layer Dropping. NeurIPS 2020.

- On the Transformer Growth for Progressive BERT Training. NACCL 2021

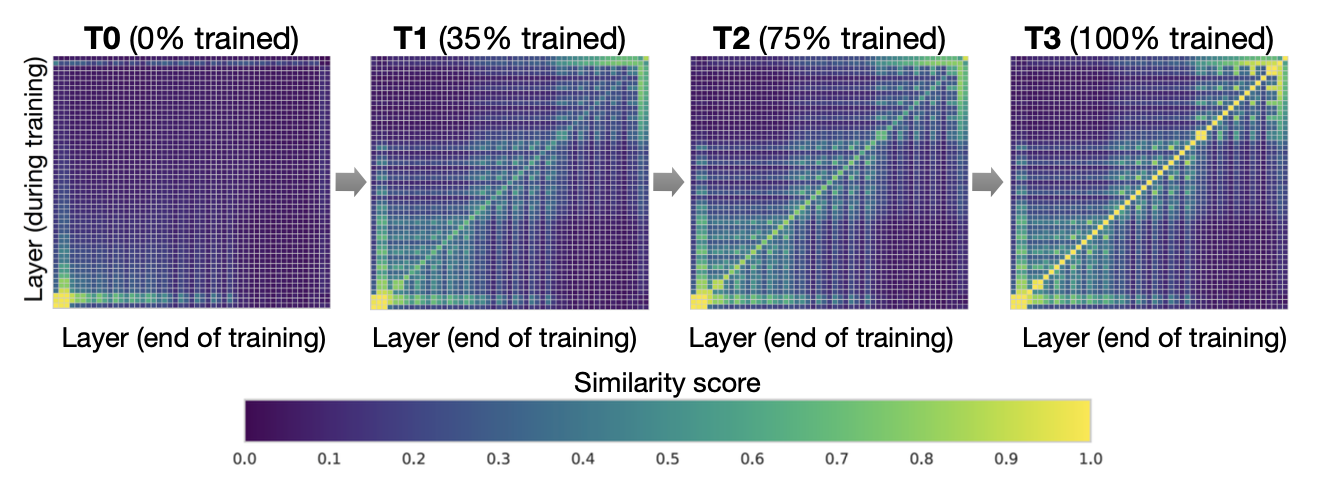

Figure 2. Interpretable Freeze Training: DNNs converge bottom-up (Results on CIFAR10 using ResNet). Each pane shows layer-by-layer similarity using SVCCA [17][18]

For example, in freeze training [17][18], neural networks usually converge from the bottom-up (i.e., not all layers need to be trained all the way through training). Figure 2 shows an example of how weights gradually stabilize during training in this approach. This observation motivates us to utilize freeze training for distributed training of Transformer models to accelerate training by dynamically allocating resources to focus on a shrinking set of active layers. Such a layer freezing strategy is especially pertinent to pipeline parallelism, as excluding consecutive bottom layers from the pipeline can reduce computation, memory, and communication overhead.

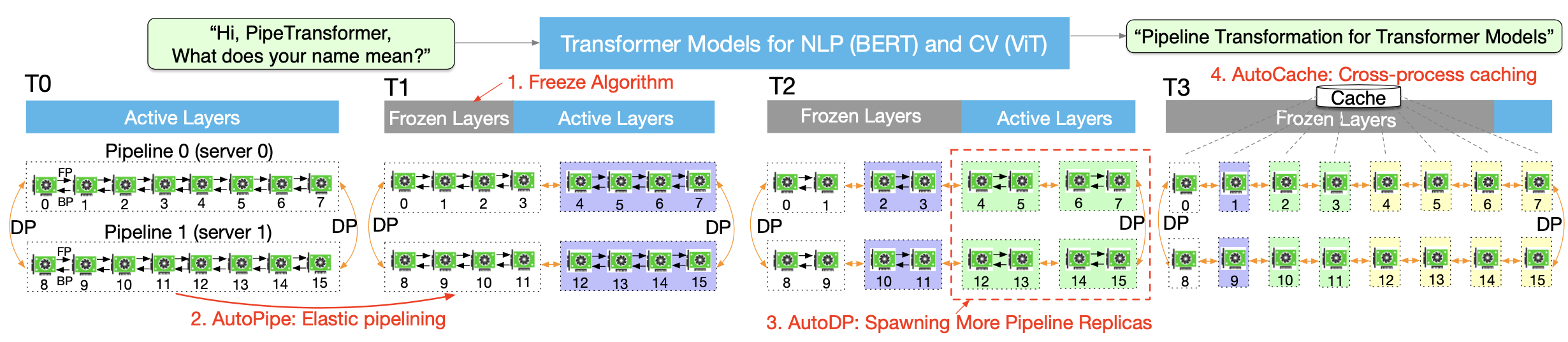

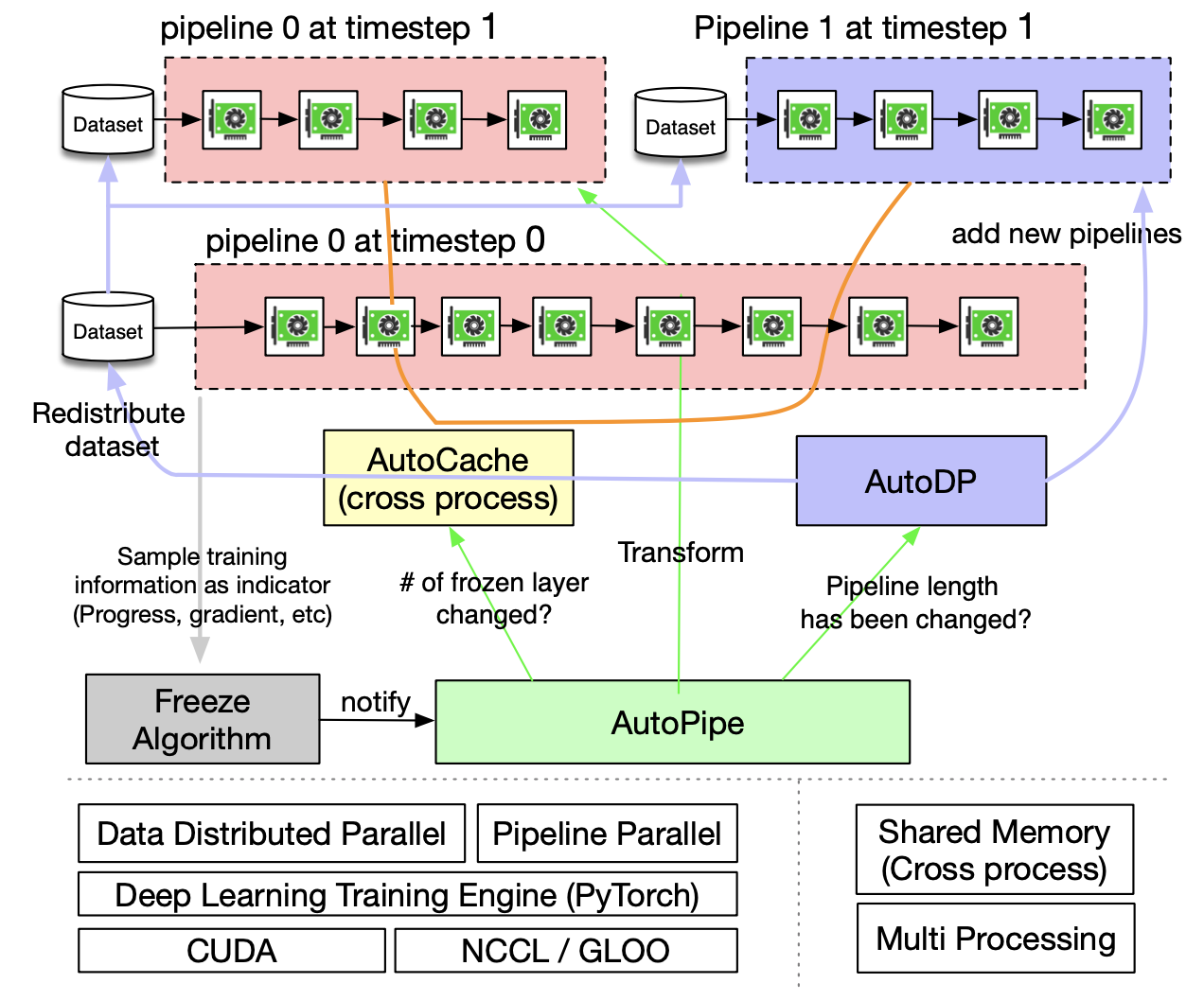

Figure 3. The process of PipeTransformer’s automated and elastic pipelining to accelerate distributed training of Transformer models

We propose PipeTransformer, an elastic pipelining training acceleration framework that automatically reacts to frozen layers by dynamically transforming the scope of the pipelined model and the number of pipeline replicas. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first paper that studies layer freezing in the context of both pipeline and data-parallel training. Figure 3 demonstrates the benefits of such a combination. First, by excluding frozen layers from the pipeline, the same model can be packed into fewer GPUs, leading to both fewer cross-GPU communications and smaller pipeline bubbles. Second, after packing the model into fewer GPUs, the same cluster can accommodate more pipeline replicas, increasing the width of data parallelism. More importantly, the speedups acquired from these two benefits are multiplicative rather than additive, further accelerating the training.

The design of PipeTransformer faces four major challenges. First, the freeze algorithm must make on-the-fly and adaptive freezing decisions; however, existing work [17][18] only provides a posterior analysis tool. Second, the efficiency of pipeline re-partitioning results is influenced by multiple factors, including partition granularity, cross-partition activation size, and the chunking (the number of micro-batches) in mini-batches, which require reasoning and searching in a large solution space. Third, to dynamically introduce additional pipeline replicas, PipeTransformer must overcome the static nature of collective communications and avoid potentially complex cross-process messaging protocols when onboarding new processes (one pipeline is handled by one process). Finally, caching can save time for repeated forward propagation of frozen layers, but it must be shared between existing pipelines and newly added ones, as the system cannot afford to create and warm up a dedicated cache for each replica.

Figure 4: An Animation to Show the Dynamics of PipeTransformer

As shown in the animation (Figure 4), PipeTransformer is designed with four core building blocks to address the aforementioned challenges. First, we design a tunable and adaptive algorithm to generate signals that guide the selection of layers to freeze over different iterations (Freeze Algorithm). Once triggered by these signals, our elastic pipelining module (AutoPipe), then packs the remaining active layers into fewer GPUs by taking both activation sizes and variances of workloads across heterogeneous partitions (frozen layers and active layers) into account. It then splits a mini-batch into an optimal number of micro-batches based on prior profiling results for different pipeline lengths. Our next module, AutoDP, spawns additional pipeline replicas to occupy freed-up GPUs and maintains hierarchical communication process groups to attain dynamic membership for collective communications. Our final module, AutoCache, efficiently shares activations across existing and new data-parallel processes and automatically replaces stale caches during transitions.

Overall, PipeTransformer combines the Freeze Algorithm, AutoPipe, AutoDP, and AutoCache modules to provide a significant training speedup. We evaluate PipeTransformer using Vision Transformer (ViT) on ImageNet and BERT on GLUE and SQuAD datasets. Our results show that PipeTransformer attains up to 2.83-fold speedup without losing accuracy. We also provide various performance analyses for a more comprehensive understanding of our algorithmic and system-wise design. Finally, we have also developed open-source flexible APIs for PipeTransformer, which offer a clean separation among the freeze algorithm, model definitions, and training accelerations, allowing for transferability to other algorithms that require similar freezing strategies.

Overall Design

Suppose we aim to train a massive model in a distributed training system where the hybrid of pipelined model parallelism and data parallelism is used to target scenarios where either the memory of a single GPU device cannot hold the model, or if loaded, the batch size is small enough to avoid running out of memory. More specifically, we define our settings as follows:

Training task and model definition. We train Transformer models (e.g., Vision Transformer, BERT on large-scale image or text datasets. The Transformer model mathcal{F} has L layers, in which the i th layer is composed of a forward computation function f_i and a corresponding set of parameters.

Training infrastructure. Assume the training infrastructure contains a GPU cluster that has N GPU servers (i.e. nodes). Each node has I GPUs. Our cluster is homogeneous, meaning that each GPU and server have the same hardware configuration. Each GPU’s memory capacity is M_\text{GPU}. Servers are connected by a high bandwidth network interface such as InfiniBand interconnect.

Pipeline parallelism. In each machine, we load a model \mathcal{F} into a pipeline \mathcal{P} which has Kpartitions (K also represents the pipeline length). The kth partition p_k consists of consecutive layers. We assume each partition is handled by a single GPU device. 1 \leq K \leq I, meaning that we can build multiple pipelines for multiple model replicas in a single machine. We assume all GPU devices in a pipeline belonging to the same machine. Our pipeline is a synchronous pipeline, which does not involve stale gradients, and the number of micro-batches is M. In the Linux OS, each pipeline is handled by a single process. We refer the reader to GPipe [10] for more details.

Data parallelism. DDP is a cross-machine distributed data-parallel process group within R parallel workers. Each worker is a pipeline replica (a single process). The rth worker’s index (ID) is rank r. For any two pipelines in DDP, they can belong to either the same GPU server or different GPU servers, and they can exchange gradients with the AllReduce algorithm.

Under these settings, our goal is to accelerate training by leveraging freeze training, which does not require all layers to be trained throughout the duration of the training. Additionally, it may help save computation, communication, memory cost, and potentially prevent overfitting by consecutively freezing layers. However, these benefits can only be achieved by overcoming the four challenges of designing an adaptive freezing algorithm, dynamical pipeline re-partitioning, efficient resource reallocation, and cross-process caching, as discussed in the introduction.

Figure 5. Overview of PipeTransformer Training System

PipeTransformer co-designs an on-the-fly freeze algorithm and an automated elastic pipelining training system that can dynamically transform the scope of the pipelined model and the number of pipeline replicas. The overall system architecture is illustrated in Figure 5. To support PipeTransformer’s elastic pipelining, we maintain a customized version of PyTorch Pipeline. For data parallelism, we use PyTorch DDP as a baseline. Other libraries are standard mechanisms of an operating system (e.g.,multi-processing) and thus avoid specialized software or hardware customization requirements. To ensure the generality of our framework, we have decoupled the training system into four core components: freeze algorithm, AutoPipe, AutoDP, and AutoCache. The freeze algorithm (grey) samples indicators from the training loop and makes layer-wise freezing decisions, which will be shared with AutoPipe (green). AutoPipe is an elastic pipeline module that speeds up training by excluding frozen layers from the pipeline and packing the active layers into fewer GPUs (pink), leading to both fewer cross-GPU communications and smaller pipeline bubbles. Subsequently, AutoPipe passes pipeline length information to AutoDP (purple), which then spawns more pipeline replicas to increase data-parallel width, if possible. The illustration also includes an example in which AutoDP introduces a new replica (purple). AutoCache (orange edges) is a cross-pipeline caching module, as illustrated by connections between pipelines. The source code architecture is aligned with Figure 5 for readability and generality.

Implementation Using PyTorch APIs

As can be seen from Figure 5, PipeTransformers contain four components: Freeze Algorithm, AutoPipe, AutoDP, and AutoCache. Among them, AutoPipe and AutoDP relies on PyTorch DDP (torch.nn.parallel.DistributedDataParallel) [1] and Pipeline (torch.distributed.pipeline), respectively. In this blog, we only highlight the key implementation details of AutoPipe and AutoDP. For details of Freeze Algorithm and AutoCache, please refer to our paper.

AutoPipe: Elastic Pipelining

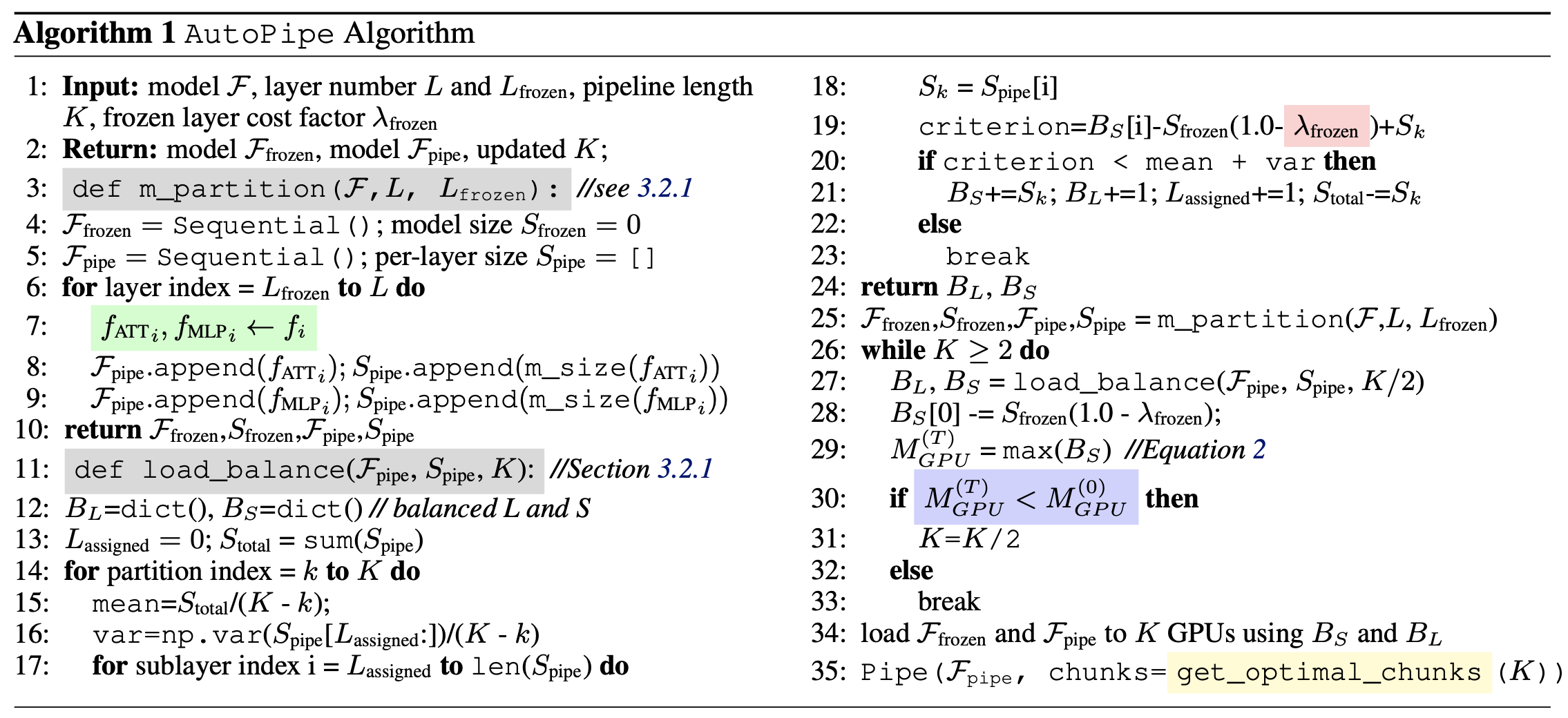

AutoPipe can accelerate training by excluding frozen layers from the pipeline and packing the active layers into fewer GPUs. This section elaborates on the key components of AutoPipe that dynamically 1) partition pipelines, 2) minimize the number of pipeline devices, and 3) optimize mini-batch chunk size accordingly.

Basic Usage of PyTorch Pipeline

Before diving into details of AutoPipe, let us warm up the basic usage of PyTorch Pipeline (torch.distributed.pipeline.sync.Pipe, see this tutorial). More specially, we present a simple example to understand the design of Pipeline in practice:

# Step 1: build a model including two linear layers

fc1 = nn.Linear(16, 8).cuda(0)

fc2 = nn.Linear(8, 4).cuda(1)

# Step 2: wrap the two layers with nn.Sequential

model = nn.Sequential(fc1, fc2)

# Step 3: build Pipe (torch.distributed.pipeline.sync.Pipe)

model = Pipe(model, chunks=8)

# do training/inference

input = torch.rand(16, 16).cuda(0)

output_rref = model(input)

In this basic example, we can see that before initializing Pipe, we need to partition the model nn.Sequential into multiple GPU devices and set optimal chunk number (chunks). Balancing computation time across partitions is critical to pipeline training speed, as skewed workload distributions across stages can lead to stragglers and forcing devices with lighter workloads to wait. The chunk number may also have a non-trivial influence on the throughput of the pipeline.

Balanced Pipeline Partitioning

In dynamic training system such as PipeTransformer, maintaining optimally balanced partitions in terms of parameter numbers does not guarantee the fastest training speed because other factors also play a crucial role:

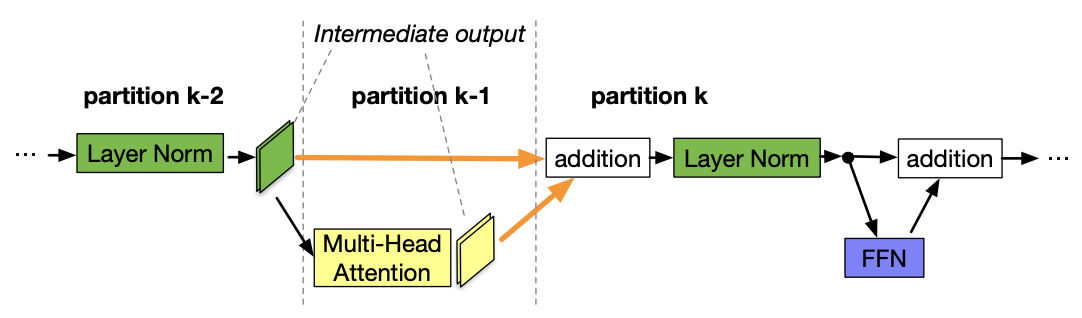

Figure 6. The partition boundary is in the middle of a skip connection

-

Cross-partition communication overhead. Placing a partition boundary in the middle of a skip connection leads to additional communications since tensors in the skip connection must now be copied to a different GPU. For example, with BERT partitions in Figure 6, partition k must take intermediate outputs from both partition k-2 and partition k-1. In contrast, if the boundary is placed after the addition layer, the communication overhead between partition k-1 and k is visibly smaller. Our measurements show that having cross-device communication is more expensive than having slightly imbalanced partitions (see the Appendix in our paper). Therefore, we do not consider breaking skip connections (highlighted separately as an entire attention layer and MLP layer in green color at line 7 in Algorithm 1.

-

Frozen layer memory footprint. During training, AutoPipe must recompute partition boundaries several times to balance two distinct types of layers: frozen layers and active layers. The frozen layer’s memory cost is a fraction of that inactive layer, given that the frozen layer does not need backward activation maps, optimizer states, and gradients. Instead of launching intrusive profilers to obtain thorough metrics on memory and computational cost, we define a tunable cost factor lambda_{\text{frozen}} to estimate the memory footprint ratio of a frozen layer over the same active layer. Based on empirical measurements in our experimental hardware, we set it to \frac{1}{6}.

Based on the above two considerations, AutoPipe balances pipeline partitions based on parameter sizes. More specifically, AutoPipe uses a greedy algorithm to allocate all frozen and active layers to evenly distribute partitioned sublayers into K GPU devices. Pseudocode is described as the load\_balance() function in Algorithm 1. The frozen layers are extracted from the original model and kept in a separate model instance \mathcal{F}_{\text{frozen}} in the first device of a pipeline.

Note that the partition algorithm employed in this paper is not the only option; PipeTransformer is modularized to work with any alternatives.

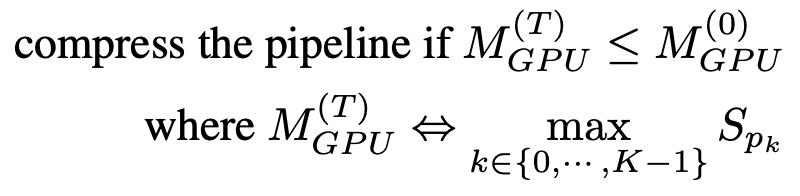

Pipeline Compression

Pipeline compression helps to free up GPUs to accommodate more pipeline replicas and reduce the number of cross-device communications between partitions. To determine the timing of compression, we can estimate the memory cost of the largest partition after compression, and then compare it with that of the largest partition of a pipeline at timestep T=0. To avoid extensive memory profiling, the compression algorithm uses the parameter size as a proxy for the training memory footprint. Based on this simplification, the criterion of pipeline compression is as follows:

Once the freeze notification is received, AutoPipe will always attempt to divide the pipeline length K by 2 (e.g., from 8 to 4, then 2). By using \frac{K}{2} as the input, the compression algorithm can verify if the result satisfies the criterion in Equation (1). Pseudocode is shown in lines 25-33 in Algorithm 1. Note that this compression makes the acceleration ratio exponentially increase during training, meaning that if a GPU server has a larger number of GPUs (e.g., more than 8), the acceleration ratio will be further amplified.

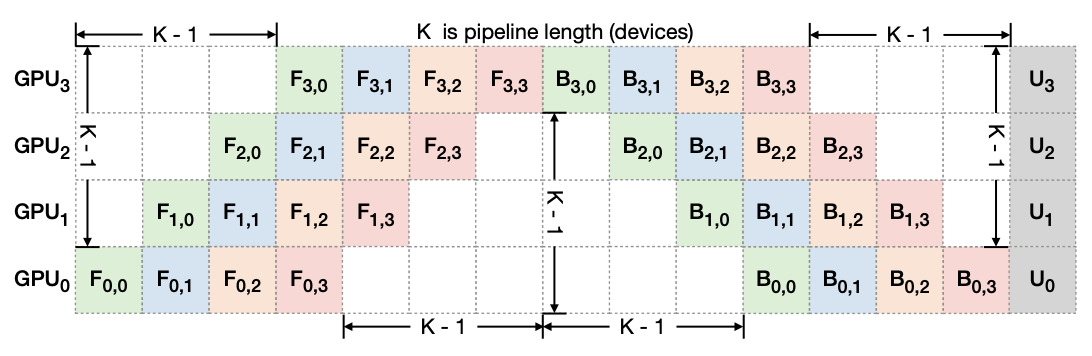

Figure 7. Pipeline Bubble: F_{d,b}, and U_d" denote forward, backward, and the optimizer update of micro-batch b on device d, respectively. The total bubble size in each iteration is K-1 times per micro-batch forward and backward cost.

Additionally, such a technique can also speed up training by shrinking the size of pipeline bubbles. To explain bubble sizes in a pipeline, Figure 7 depicts how 4 micro-batches run through a 4-device pipeline K = 4. In general, the total bubble size is (K-1) times per micro-batch forward and backward cost. Therefore, it is clear that shorter pipelines have smaller bubble sizes.

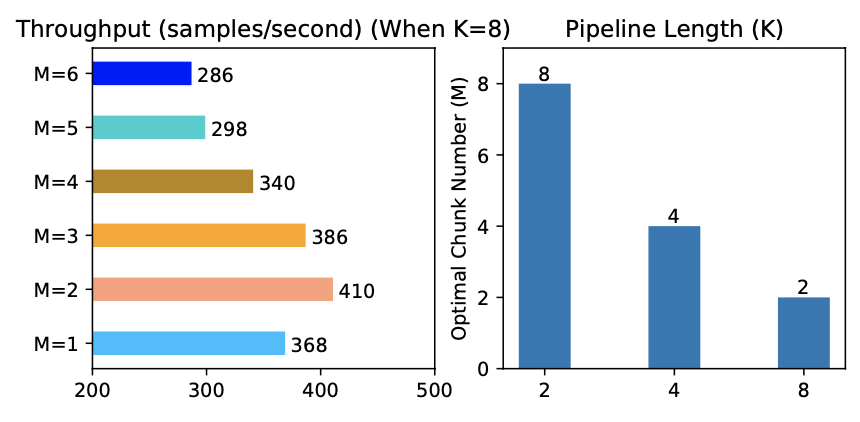

Dynamic Number of Micro-Batches

Prior pipeline parallel systems use a fixed number of micro-batches per mini-batch (M ). GPipe suggests M \geq 4 \times K, where K is the number of partitions (pipeline length). However, given that PipeTransformer dynamically configures K, we find it to be sub-optimal to maintain a static M during training. Moreover, when integrated with DDP, the value of M also has an impact on the efficiency of DDP gradient synchronizations. Since DDP must wait for the last micro-batch to finish its backward computation on a parameter before launching its gradient synchronization, finer micro-batches lead to a smaller overlap between computation and communication. Hence, instead of using a static value, PipeTransformer searches for optimal M on the fly in the hybrid of DDP environment by enumerating M values ranging from K to 6K. For a specific training environment, the profiling needs only to be done once (see Algorithm 1 line 35).

For the complete source code, please refer to https://github.com/Distributed-AI/PipeTransformer/blob/master/pipe_transformer/pipe/auto_pipe.py.

AutoDP: Spawning More Pipeline Replicas

As AutoPipe compresses the same pipeline into fewer GPUs, AutoDP can automatically spawn new pipeline replicas to increase data-parallel width.

Despite the conceptual simplicity, subtle dependencies on communications and states require careful design. The challenges are threefold:

-

DDP Communication: Collective communications in PyTorch DDP requires static membership, which prevents new pipelines from connecting with existing ones;

-

State Synchronization: newly activated processes must be consistent with existing pipelines in the training progress (e.g., epoch number and learning rate), weights and optimizer states, the boundary of frozen layers, and pipeline GPU range;

-

Dataset Redistribution: the dataset should be re-balanced to match a dynamic number of pipelines. This not only avoids stragglers but also ensures that gradients from all DDP processes are equally weighted.

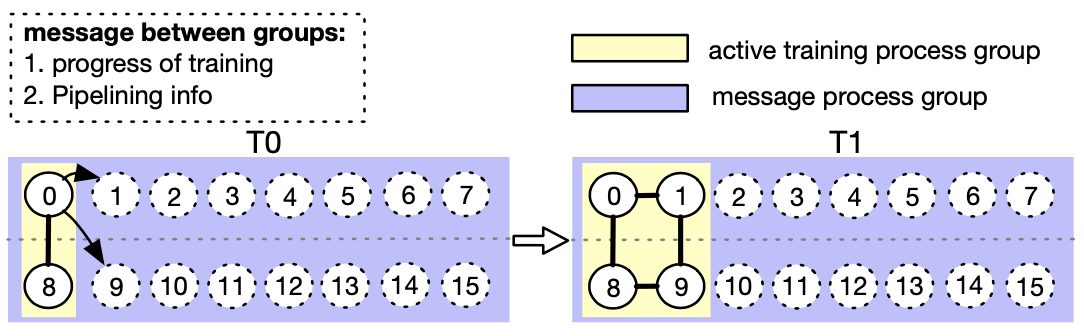

Figure 8. AutoDP: handling dynamical data-parallel with messaging between double process groups (Process 0-7 belong to machine 0, while process 8-15 belong to machine 1)

To tackle these challenges, we create double communication process groups for DDP. As in the example shown in Figure 8, the message process group (purple) is responsible for light-weight control messages and covers all processes, while the active training process group (yellow) only contains active processes and serves as a vehicle for heavy-weight tensor communications during training. The message group remains static, whereas the training group is dismantled and reconstructed to match active processes. In T0, only processes 0 and 8 are active. During the transition to T1, process 0 activates processes 1 and 9 (newly added pipeline replicas) and synchronizes necessary information mentioned above using the message group. The four active processes then form a new training group, allowing static collective communications adaptive to dynamic memberships. To redistribute the dataset, we implement a variant of DistributedSampler that can seamlessly adjust data samples to match the number of active pipeline replicas.

The above design also naturally helps to reduce DDP communication overhead. More specifically, when transitioning from T0 to T1, processes 0 and 1 destroy the existing DDP instances, and active processes construct a new DDP training group using a cached pipelined model (AutoPipe stores frozen model and cached model separately).

We use the following APIs to implement the design above.

import torch.distributed as dist

from torch.nn.parallel import DistributedDataParallel as DDP

# initialize the process group (this must be called in the initialization of PyTorch DDP)

dist.init_process_group(init_method='tcp://' + str(self.config.master_addr) + ':' +

str(self.config.master_port), backend=Backend.GLOO, rank=self.global_rank, world_size=self.world_size)

...

# create active process group (yellow color)

self.active_process_group = dist.new_group(ranks=self.active_ranks, backend=Backend.NCCL, timeout=timedelta(days=365))

...

# create message process group (yellow color)

self.comm_broadcast_group = dist.new_group(ranks=[i for i in range(self.world_size)], backend=Backend.GLOO, timeout=timedelta(days=365))

...

# create DDP-enabled model when the number of data-parallel workers is changed. Note:

# 1. The process group to be used for distributed data all-reduction.

If None, the default process group, which is created by torch.distributed.init_process_group, will be used.

In our case, we set it as self.active_process_group

# 2. device_ids should be set when the pipeline length = 1 (the model resides on a single CUDA device).

self.pipe_len = gpu_num_per_process

if gpu_num_per_process > 1:

model = DDP(model, process_group=self.active_process_group, find_unused_parameters=True)

else:

model = DDP(model, device_ids=[self.local_rank], process_group=self.active_process_group, find_unused_parameters=True)

# to broadcast message among processes, we use dist.broadcast_object_list

def dist_broadcast(object_list, src, group):

"""Broadcasts a given object to all parties."""

dist.broadcast_object_list(object_list, src, group=group)

return object_list

For the complete source code, please refer to https://github.com/Distributed-AI/PipeTransformer/blob/master/pipe_transformer/dp/auto_dp.py.

Experiments

This section first summarizes experiment setups and then evaluates PipeTransformer using computer vision and natural language processing tasks.

Hardware. Experiments were conducted on 2 identical machines connected by InfiniBand CX353A (5GB/s), where each machine is equipped with 8 NVIDIA Quadro RTX 5000 (16GB GPU memory). GPU-to-GPU bandwidth within a machine (PCI 3.0, 16 lanes) is 15.754GB/s.

Implementation. We used PyTorch Pipe as a building block. The BERT model definition, configuration, and related tokenizer are from HuggingFace 3.5.0. We implemented Vision Transformer using PyTorch by following its TensorFlow implementation. More details can be found in our source code.

Models and Datasets. Experiments employ two representative Transformers in CV and NLP: Vision Transformer (ViT) and BERT. ViT was run on an image classification task, initialized with pre-trained weights on ImageNet21K and fine-tuned on ImageNet and CIFAR-100. BERT was run on two tasks, text classification on the SST-2 dataset from the General Language Understanding Evaluation (GLUE) benchmark, and question answering on the SQuAD v1.1 Dataset (Stanford Question Answering), which is a collection of 100k crowdsourced question/answer pairs.

Training Schemes. Given that large models normally would require thousands of GPU-days {\emph{e.g.}, GPT-3) if trained from scratch, fine-tuning downstream tasks using pre-trained models has become a trend in CV and NLP communities. Moreover, PipeTransformer is a complex training system that involves multiple core components. Thus, for the first version of PipeTransformer system development and algorithmic research, it is not cost-efficient to develop and evaluate from scratch using large-scale pre-training. Therefore, the experiments presented in this section focuses on pre-trained models. Note that since the model architectures in pre-training and fine-tuning are the same, PipeTransformer can serve both. We discussed pre-training results in the Appendix.

Baseline. Experiments in this section compare PipeTransformer to the state-of-the-art framework, a hybrid scheme of PyTorch Pipeline (PyTorch’s implementation of GPipe) and PyTorch DDP. Since this is the first paper that studies accelerating distributed training by freezing layers, there are no perfectly aligned counterpart solutions yet.

Hyper-parameters. Experiments use ViT-B/16 (12 transformer layers, 16 \times 16 input patch size) for ImageNet and CIFAR-100, BERT-large-uncased (24 layers) for SQuAD 1.1, and BERT-base-uncased (12 layers) for SST-2. With PipeTransformer, ViT and BERT training can set the per-pipeline batch size to around 400 and 64, respectively. Other hyperparameters (e.g., epoch, learning rate) for all experiments are presented in Appendix.

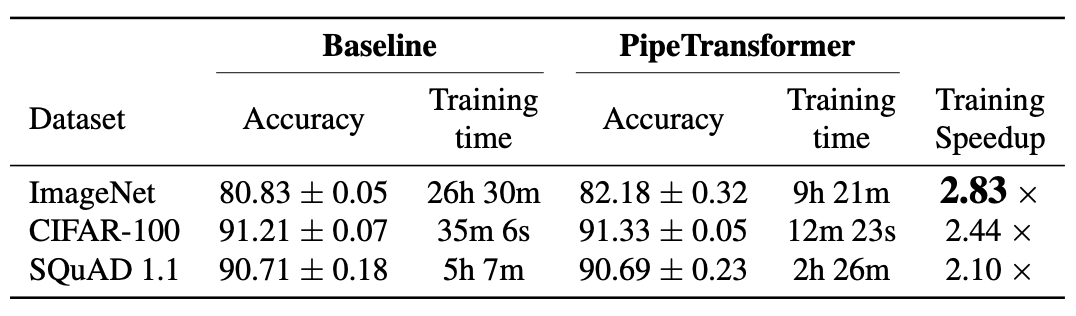

Overall Training Acceleration

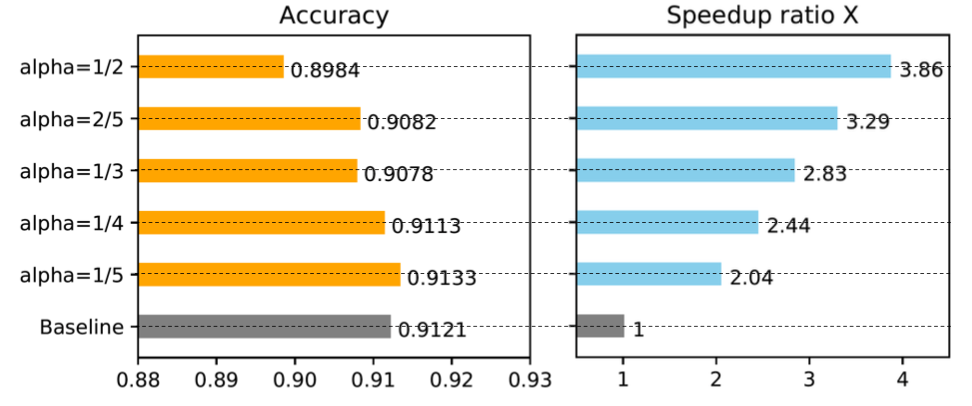

We summarize the overall experimental results in the table above. Note that the speedup we report is based on a conservative \alpha \frac{1}{3} value that can obtain comparable or even higher accuracy. A more aggressive \alpha (\frac{2}{5}, \frac{1}{2}) can obtain a higher speedup but may lead to a slight loss in accuracy. Note that the model size of BERT (24 layers) is larger than ViT-B/16 (12 layers), thus it takes more time for communication.

Performance Analysis

Speedup Breakdown

This section presents evaluation results and analyzes the performance of different components in \autopipe. More experimental results can be found in the Appendix.

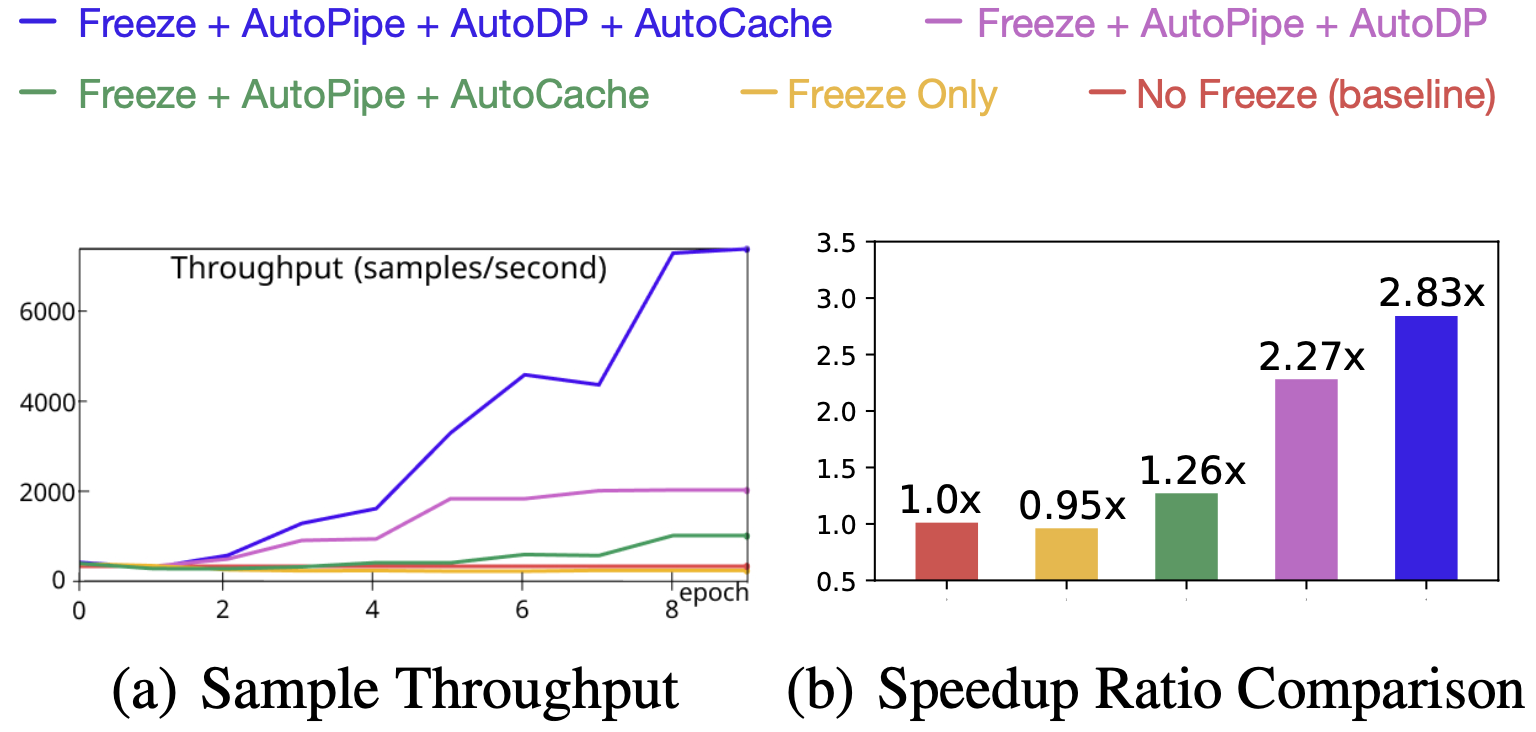

Figure 9. Speedup Breakdown (ViT on ImageNet)

To understand the efficacy of all four components and their impacts on training speed, we experimented with different combinations and used their training sample throughput (samples/second) and speedup ratio as metrics. Results are illustrated in Figure 9. Key takeaways from these experimental results are:

- the main speedup is the result of elastic pipelining which is achieved through the joint use of AutoPipe and AutoDP;

- AutoCache’s contribution is amplified by AutoDP;

- freeze training alone without system-wise adjustment even downgrades the training speed.

Tuning \alpha in Freezing Algorithm

Figure 10. Tuning \alpha in Freezing Algorithm

We ran experiments to show how the \alpha in the freeze algorithms influences training speed. The result clearly demonstrates that a larger \alpha (excessive freeze) leads to a greater speedup but suffers from a slight performance degradation. In the case shown in Figure 10, where \alpha=1/5, freeze training outperforms normal training and obtains a 2.04-fold speedup. We provide more results in the Appendix.

Optimal Chunks in the elastic pipeline

Figure 11. Optimal chunk number in the elastic pipeline

We profiled the optimal number of micro-batches M for different pipeline lengths K. Results are summarized in Figure 11. As we can see, different K values lead to different optimal M, and the throughput gaps across different M values are large (as shown when K=8), which confirms the necessity of an anterior profiler in elastic pipelining.

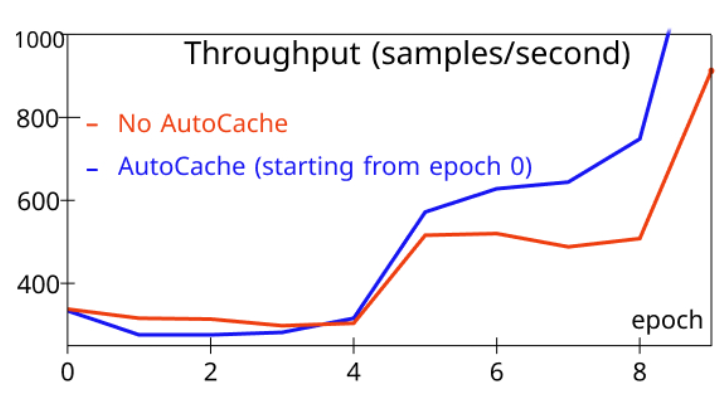

Understanding the Timing of Caching

Figure 12. the timing of caching

To evaluate AutoCache, we compared the sample throughput of training that activates AutoCache from epoch 0 (blue) with the training job without AutoCache (red). Figure 12 shows that enabling caching too early can slow down training, as caching can be more expensive than the forward propagation on a small number of frozen layers. After more layers are frozen, caching activations clearly outperform the corresponding forward propagation. As a result, AutoCache uses a profiler to determine the proper timing to enable caching. In our system, for ViT (12 layers), caching starts from 3 frozen layers, while for BERT (24 layers), caching starts from 5 frozen layers.

For more detailed experimental analysis, please refer to our paper.

Summarization

This blog introduces PipeTransformer, a holistic solution that combines elastic pipeline-parallel and data-parallel for distributed training using PyTorch Distributed APIs. More specifically, PipeTransformer incrementally freezes layers in the pipeline, packs remaining active layers into fewer GPUs, and forks more pipeline replicas to increase the data-parallel width. Evaluations on ViT and BERT models show that compared to the state-of-the-art baseline, PipeTransformer attains up to 2.83× speedups without accuracy loss.

Reference

[1] Li, S., Zhao, Y., Varma, R., Salpekar, O., Noordhuis, P., Li,T., Paszke, A., Smith, J., Vaughan, B., Damania, P., et al. Pytorch Distributed: Experiences on Accelerating Dataparallel Training. Proceedings of the VLDB Endowment,13(12), 2020

[2] Devlin, J., Chang, M. W., Lee, K., and Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In NAACL-HLT, 2019

[3] Dosovitskiy, A., Beyer, L., Kolesnikov, A., Weissenborn, D., Zhai, X., Unterthiner, T., Dehghani, M., Minderer, M., Heigold, G., Gelly, S., et al. An image is Worth 16x16 words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale.

[4] Brown, T. B., Mann, B., Ryder, N., Subbiah, M., Kaplan, J., Dhariwal, P., Neelakantan, A., Shyam, P., Sastry, G., Askell, A., et al. Language Models are Few-shot Learners.

[5] Lepikhin, D., Lee, H., Xu, Y., Chen, D., Firat, O., Huang, Y., Krikun, M., Shazeer, N., and Chen, Z. Gshard: Scaling Giant Models with Conditional Computation and Automatic Sharding.

[6] Li, M., Andersen, D. G., Park, J. W., Smola, A. J., Ahmed, A., Josifovski, V., Long, J., Shekita, E. J., and Su, B. Y. Scaling Distributed Machine Learning with the Parameter Server. In 11th {USENIX} Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation ({OSDI} 14), pp. 583–598, 2014.

[7] Jiang, Y., Zhu, Y., Lan, C., Yi, B., Cui, Y., and Guo, C. A Unified Architecture for Accelerating Distributed DNN Training in Heterogeneous GPU/CPU Clusters. In 14th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 20), pp. 463–479. USENIX Association, November 2020. ISBN 978-1-939133-19- 9.

[8] Kim, S., Yu, G. I., Park, H., Cho, S., Jeong, E., Ha, H., Lee, S., Jeong, J. S., and Chun, B. G. Parallax: Sparsity-aware Data Parallel Training of Deep Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Fourteenth EuroSys Conference 2019, pp. 1–15, 2019.

[9] Kim, C., Lee, H., Jeong, M., Baek, W., Yoon, B., Kim, I., Lim, S., and Kim, S. TorchGPipe: On-the-fly Pipeline Parallelism for Training Giant Models.

[10] Huang, Y., Cheng, Y., Bapna, A., Firat, O., Chen, M. X., Chen, D., Lee, H., Ngiam, J., Le, Q. V., Wu, Y., et al. Gpipe: Efficient Training of Giant Neural Networks using Pipeline Parallelism.

[11] Park, J. H., Yun, G., Yi, C. M., Nguyen, N. T., Lee, S., Choi, J., Noh, S. H., and ri Choi, Y. Hetpipe: Enabling Large DNN Training on (whimpy) Heterogeneous GPU Clusters through Integration of Pipelined Model Parallelism and Data Parallelism. In 2020 USENIX Annual Technical Conference (USENIX ATC 20), pp. 307–321. USENIX Association, July 2020. ISBN 978-1-939133- 14-4.

[12] Narayanan, D., Harlap, A., Phanishayee, A., Seshadri, V., Devanur, N. R., Ganger, G. R., Gibbons, P. B., and Zaharia, M. Pipedream: Generalized Pipeline Parallelism for DNN Training. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM Symposium on Operating Systems Principles, SOSP ’19, pp. 1–15, New York, NY, USA, 2019. Association for Computing Machinery. ISBN 9781450368735. doi: 10.1145/3341301.3359646.

[13] Lepikhin, D., Lee, H., Xu, Y., Chen, D., Firat, O., Huang, Y., Krikun, M., Shazeer, N., and Chen, Z. Gshard: Scaling Giant Models with Conditional Computation and Automatic Sharding.

[14] Shazeer, N., Cheng, Y., Parmar, N., Tran, D., Vaswani, A., Koanantakool, P., Hawkins, P., Lee, H., Hong, M., Young, C., Sepassi, R., and Hechtman, B. Mesh-Tensorflow: Deep Learning for Supercomputers. In Bengio, S., Wallach, H., Larochelle, H., Grauman, K., Cesa-Bianchi, N., and Garnett, R. (eds.), Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, volume 31, pp. 10414–10423. Curran Associates, Inc., 2018.

[15] Shoeybi, M., Patwary, M., Puri, R., LeGresley, P., Casper, J., and Catanzaro, B. Megatron-LM: Training Multi-billion Parameter Language Models using Model Parallelism.

[16] Rajbhandari, S., Rasley, J., Ruwase, O., and He, Y. ZERO: Memory Optimization towards Training a Trillion Parameter Models.

[17] Raghu, M., Gilmer, J., Yosinski, J., and Sohl Dickstein, J. Svcca: Singular Vector Canonical Correlation Analysis for Deep Learning Dynamics and Interpretability. In NIPS, 2017.

[18] Morcos, A., Raghu, M., and Bengio, S. Insights on Representational Similarity in Neural Networks with Canonical Correlation. In Bengio, S., Wallach, H., Larochelle, H., Grauman, K., Cesa-Bianchi, N., and Garnett, R. (eds.), Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 31, pp. 5732–5741. Curran Associates, Inc., 2018.